My life path has taught me many uncertainties. What is uncertainty? Well, I am glad that you asked. In this context, uncertainty is something with pros and cons that is up for a rational debate. Experience has also taught me that rare issues are beyond dispute; such matters fall in the category of “I know this for certain.” Unfortunately for Black men, one of the things that I know for sure is that the vast majority of us have tangled with a persistent enemy that will leave you broken, hopeless, and in many cases suicidal. What makes this enemy so dangerous is the fact that his ongoing attacks are ruthless and relentless.

This invisible opponent’s incredible power is attributable to his ability to use everything, including the few elements in Black male lives to execute further damage. Such attacks are invisible to outsiders.

Black men tend to suffer in dark echo chambers that prevent light entrance yet manage to magnify negative thoughts.

Of course, the enemy I speak of is depression. This dastardly disorder cares not about your socioeconomic status, age, sexual orientation, marital status. Well, you get the picture. Depression is the opportunist of all opportunists.

Predictably, I, like so many other Black men of my generation, did not understand my initial exposure to this chameleon.

Please let me explain.

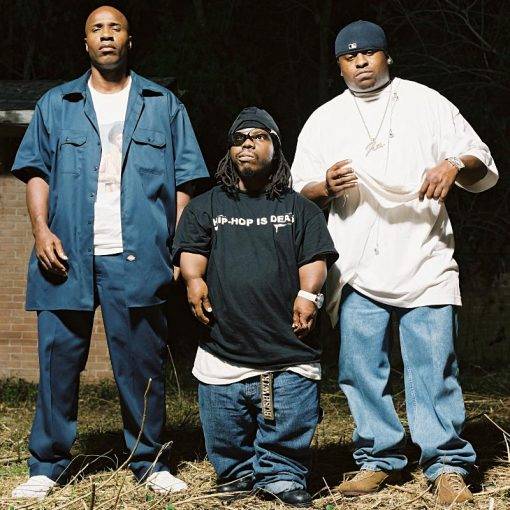

In 1991, Geto Boys released the album We Can’t Be Stopped, the classic song My Mind Playing Tricks on Me was included in that musical compilation. There is no room to argue against the fact that Scarface, Willie D., and Bushwick Bill rhymed over a hypnotic tune. In hindsight, the music was so good that it caused most listeners to ignore the lyrical content. Maybe if My Mind Playing Tricks on Me were released Accapella, Black men would have understood that the song places a much-needed spotlight on depression and the myriad ways it plays tricks with one’s mind. Just consider the opening lyrics delivered by Scarface, the South Park Stalker.

… I sit alone in my four-cornered room

Staring at candles

… At night I can’t sleep, I toss and turn

Candle sticks in the dark, visions of bodies being burned

Four walls just staring at a nigga

I’m paranoid, sleeping with my finger on the trigger

My mother’s always stressing I ain’t living right

But I ain’t going out without a fight

See, everytime my eyes close

I start sweatin, and blood starts comin out my nose

… It’s somebody watchin’ the ak’

But I don’t know who it is, so I’m watchin my back

I can see him when I’m deep in the covers

When I awake I don’t see the motherfucker

He owns a black hat like I own

A black suit and a cane like my own

Some might say “take a chill, b”

But fuck that shit, there’s a nigga trying to kill me

… I’m pumping in the clip when the wind blows

Every twenty seconds got me peeping out my window

Investigating the joint for traps

Checking my telephone for taps

I’m staring at the woman on the corner

It’s fucked up when your mind is playing tricks on you

As with most things impacting Black males, African-American men receive more than their fair share of the bad and a small portion of the positive.

The following facts provided by an initiative called Brother, You’re on My Mind shows the consequence of this unfair arrangement. The initiative, a partnership between the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities and the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., reports the following realities.

- Adult African Americans are 20 percent more likely to report severe psychological distress than adult whites.

- Adult African Americans living in poverty are two to three times more likely to report severe psychological distress than those not living in poverty.

- Suicide is the third leading cause of death for African American males ages 15 to 24.

- African American men ages 20 to 24 have the highest suicide rate among African Americans of all ages, male and female.

- African American teenagers are more likely to attempt suicide than are white teenagers.

- Young African Americans are much less likely than White youth to have used a mental health service in the year during which they seriously thought about or attempted suicide.

After viewing the above facts, one cannot conclude anything else than Black America in general, and Black men of all ages are in crisis.

Unfortunately for Black men, the decades-old stigma associated with any engagement with a mental health professional problematizes an obvious solution. Black men will attempt to fight through these issues via an assortment of self-medication efforts that include, but are not limited to, numbing themselves with massive doses of alcohol, food, promiscuity, rage, and drugs. If things could not be any worse, Black men willing to receive professional help have limited choices. Only 2% of 41,000 American psychiatrists are Black.

No one is coming to save Black men from this mental health crisis or any other crisis. So, we must do a much better job of checking on each other, going the extra step, and accompanying or arranging for engagement with mental health professionals. We must attempt to save each other “by any means necessary.”

James Thomas Jones III, Ph.D.

©Manhood, Race, and Culture, 2021